Food safety is the top priority for companies that produce and process chicken products in the U.S., and the industry prides itself on delivering safe, affordable and wholesome chicken both domestically and abroad. Chicken producers continue to meet food safety challenges head-on and have done an outstanding job of improving the microbiological profile of raw chicken products.

Who oversees and regulates chicken processing plants?

The Food Safety and Inspection Service (FSIS) is the public health agency within the U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA) responsible for inspection at broiler chicken processing facilities, where chickens are processed for meat. The U.S. meat and poultry inspection system complements industry efforts to ensure that the nation’s commercial supply of meat and poultry products is safe, wholesome and correctly labeled and packaged.

Rigorous food safety standards are applied to every chicken product produced in the U.S., and all imported chicken products must also meet or exceed these federal safety standards before reaching American consumers. By law, a chicken plant cannot operate without FSIS inspectors onsite.

What is HACCP?

Since 1996, the meat and poultry industries have been operating under Hazard Analysis Critical Control Point (HACCP). Originally developed for NASA to ensure the safety of food provided for astronauts in outer space, HACCP is a systematic, science-based and preventive approach to food safety that addresses potential biological, chemical and physical contamination of food products. Written HACCP plans consist of measures to protect the food from unintentional contamination at critical control points. HACCP is used in the meat and poultry industry as a preventative approach to identify potential food safety hazards so that key actions can be taken to reduce or eliminate these risks.

All plants must also, by regulation, maintain written Sanitation Standard Operating Procedures (Sanitation SOPs) to maintain the cleanliness and sanitary conditions in the food processing environment. FSIS inspectors continuously ensure that HACCP plans and Sanitation SOPs are being followed.

What is Salmonella?

Salmonella are microscopic living organisms found worldwide in cold- and warm-blooded animals and occur naturally in birds’ intestines. Salmonella may be present in a perfectly healthy bird with no negative health effects.

Salmonellosis is the infection caused by certain types of Salmonella. You can get salmonellosis by ingesting contaminated foods, being exposed to cross-contamination in the kitchen, or not properly cooking or washing raw meat, poultry, or vegetables.

Are all types of Salmonella the same?

No. There are more than 2,000 different strains of Salmonella, the majority of which are not associated with human illness. Most of these Salmonella strains do not make consumers sick if exposed to them.

But a few are. What are chicken producers doing to make sure they don’t end up on chicken products?

Proper handling and cooking in the kitchen is the last step in keeping Salmonella off chicken, not the first.

Food safety starts even before the egg. Healthy breeder hens lead to healthy eggs and healthy chicks. Measures are taken to prevent diseases from passing from hen to chick, and to ensure that natural antibodies are passed on, which help keep the birds healthy.

At the hatchery, strict sanitation measures and appropriate vaccinations, including ones for Salmonella, ensure the chicks are off to a healthy start. At the feed mill, the corn and soybean meal that chickens eat is either heat- or chemical-treated, which kills any bacteria that may be present. On the farm, farmers adhere to strict biosecurity measures and the chickens are routinely monitored by a veterinarian to keep them healthy.

At processing plants, the U.S. federal meat and poultry inspection system complements efforts by chicken processors to ensure that the nation’s commercial supply of meat and poultry products is safe, wholesome and correctly labeled and packaged. USDA FSIS inspectors are present in every chicken processing facility, as required by law.

Chicken processing facilities use a variety of strategies at key points, including:

- Written HACCP plans

- Food-grade rinses that kill or reduce the growth of bacteria and potential foodborne pathogens

- Organic sprays to cleanse the chickens and inhibit bacteria

- Strict sanitation procedures;

- Metal detectors and x-ray technology to make sure products are not contaminated with foreign material

Microbiological tests for pathogens are then conducted by companies and by FSIS at federal laboratories to help ensure that food safety systems are working properly and that all products meet USDA standards for wholesomeness.

Are these processes working? What does the data show?

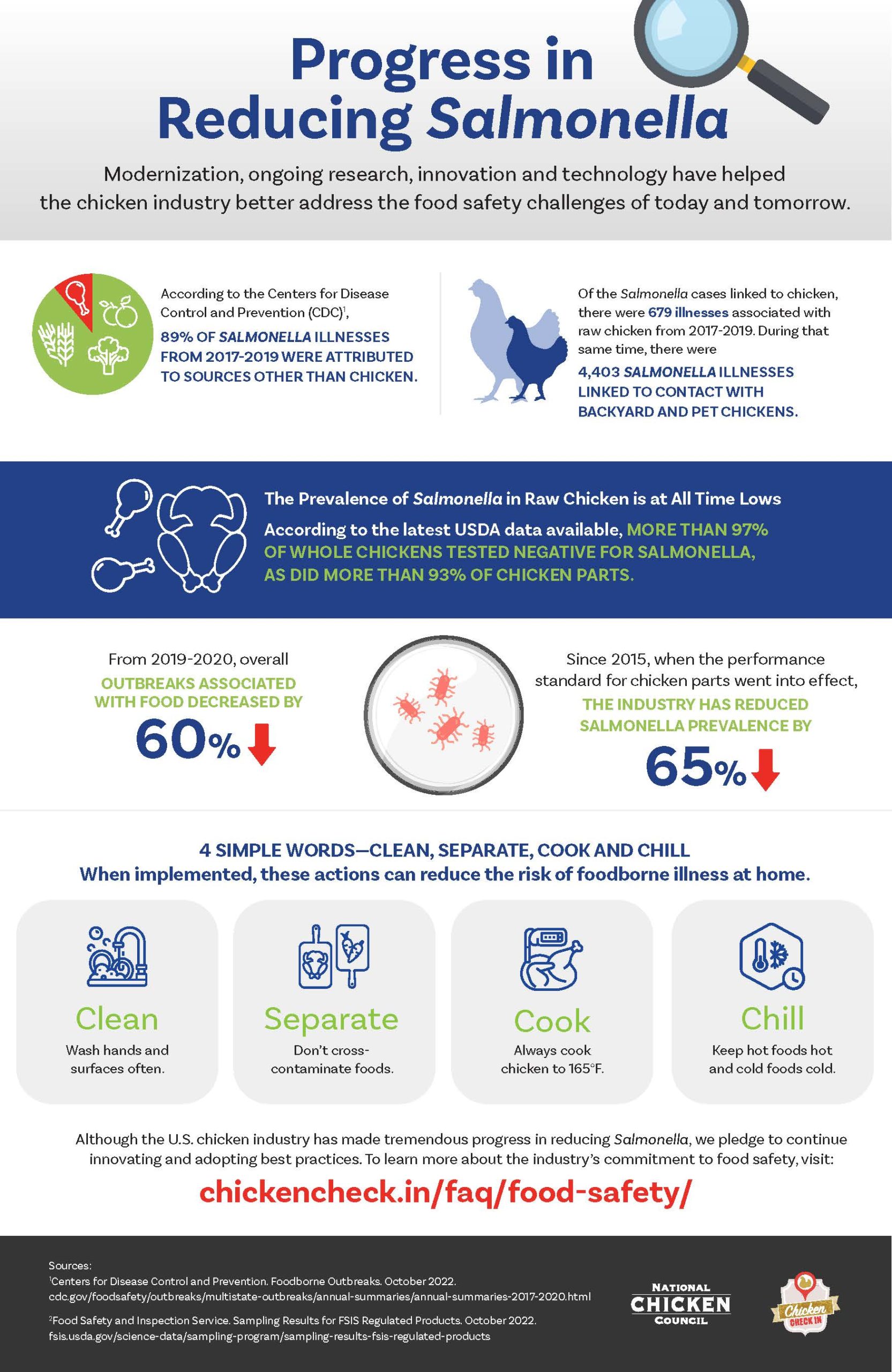

According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) and FSIS data available from July 2021 through June 2022:

- More than 97% of whole chickens tested negative for Salmonella.

- More than 90% of the industry is meeting or exceeding the FSIS performance standard for Salmonella on whole broiler carcasses.

- From 2019-2020, overall foodborne illness outbreaks decreased 60%.

Those tests are for whole chickens. What about chicken parts?

Since the fall of 2013, the entire chicken industry has been exploring new approaches and technologies to reduce contamination on chicken parts to provide the safest product possible to our consumers, including strengthened sanitation programs, temperature controls and various interventions in chicken processing. This is something the industry has been proactively working to address, and the industry is committed to working collaboratively with FSIS to continue to enhance these processes.

More than 90% of broiler establishments are meeting and exceeding the FSIS performance standard for Salmonella on chicken parts like wings, breasts and drumsticks. In fact, according to FSIS, more than 93% of chicken parts tested negative for Salmonella. And since 2015, when the performance standard for chicken parts went into effect, the industry has reduced Salmonella prevalence by 65%.

What are performance standards?

A performance standard is a metric that FSIS uses to evaluate potential presence of pathogens on poultry and other FSIS-regulated products. In the case for poultry, the pathogen is Salmonella. FSIS expects poultry establishments to meet Salmonella performance standards as a means of verifying that production systems are effective in controlling contamination by this organism. Agency inspection personnel conduct Salmonella testing in poultry establishments to verify compliance with the Salmonella standard.

What are some actions that FSIS may take if inspectors document food safety problems at a chicken plant?

FSIS operates a comprehensive food safety enforcement regime. Multiple FSIS inspectors are in each chicken processing facility any time the facility is processing chicken. FSIS inspectors inspect every single product produced, and they also use scientifically based inspectional procedures to assess a facility’s processes, equipment, and sanitary controls. FSIS has a number of tools at its disposal to address potential issues, ranging from issuing citations (noncompliance records) that require immediate corrective and preventive actions, detaining violative product, conducting intensified health hazard evaluations and intensified inspections, and, if needed, suspending a facility’s ability to operate. Much of FSIS’s inspectional approach is focused on proactively identifying potential issues before they create a food safety problem, and processors are quick to address issues raised by FSIS.

FSIS also works with CDC and other public health partners to conduct ongoing foodborne illness surveillance and traceback, and processing facilities work with FSIS to conduct recalls when necessary.

Is it true that 80% of the chicken sold in the U.S is “chicken parts?”

According to the National Chicken Council, 11% are marketed as whole chickens, 40% parts (raw breasts, wings, drumsticks, etc.), and 49% further processed/value added. The latter includes nuggets, strips, patties and other fully cooked products that contain chicken. FSIS has zero tolerance for certain pathogens, including Salmonella and Listeria monocytogenes, in cooked and ready-to-eat products, such as chicken lunch meat and fully cooked nuggets and strips.

Is chicken the leading cause of Salmonella illnesses?

Based on findings from the CDC and FSIS, 89% of Salmonella illnesses from 2017-2019 were associated with food products like seeded vegetables, row crop vegetables, eggs, fruit and other foods—not chicken.

And many recorded Salmonella illnesses are attributed to backyard and pet chickens rather than the chicken you’ll find at the grocery store. From 2017-2019, there were 679 Salmonella outbreaks linked to raw chicken. During that same time, there were 4,403 Salmonella illnesses linked to contact with backyard and pet chickens.

Are chickens labeled “organic” more safe and lower in Salmonella bacteria?

Any raw agricultural product, including fresh fruit, vegetables, meat and poultry, is susceptible to naturally occurring bacteria. Whether it’s labeled “organic,” “natural,” purchased in the grocery store or at your local farmers’ market, there is the potential that a raw agricultural commodity could make us sick, if improperly handled or cooked.

The USDA notes that there is no scientific information demonstrating more or less Salmonella in one type of chicken versus another. Consumers should use proper handling and cooking instructions for all raw meat and poultry products. When cooked to an internal temperature of 165F as measured by a meat thermometer in the thickest portion of the product, all chicken is safe to consume.

Why not treat Salmonella like the government treats E. coli O157:H7, e.g. declare it an adulterant?

FSIS has previously used zero tolerance policies to control E. coli O157 in ground beef. Some have suggested that this serves as precedent for similar action for Salmonella in raw meat and poultry products. (Only E. coli that causes foodborne illness has a zero tolerance, like the O157:H7 strain.)

Many food safety experts also say comparing E. coli in beef to Salmonella in chicken—or even European poultry industries to the U.S. industry—is like comparing apples and oranges. In fact, there are significant differences between pathogenic E. coli in raw ground beef and Salmonella in chicken. E. coli contaminates beef through cross contact with materials during the harvesting process, and from there it can get mixed into the interior of products like a ground beef patty. Because intentionally undercooking ground beef (such as ordering a hamburger medium rate) will not destroy any E. coli that might be in the middle of the patty, FSIS has implemented a “zero tolerance” policy for certain pathogenic E. coli strains in these products. Chicken is quite different. Salmonella is a natural part of the chicken biome, and it enters the processing facility in the chicken rather than through cross contamination with outside materials during processing. Chicken is customarily “cooked through” to an internal temperature of at least 165F, which destroys any Salmonella that may be present. So a zero-tolerance policy is neither necessary nor feasible. Experts agrees. According to a 2015 report by the University of Minnesota’s Food Policy Research Center, “Enacting zero tolerance policies for Salmonella will not necessarily produce the desired public health outcomes.”

Although there are critical differences between E. coli in ground beef and Salmonella on chicken, chicken processors take a variety of steps to reduce Salmonella levels before and throughout processing. Moreover, FSIS implements a zero-tolerance policy for visible fecal contamination of chicken carcasses prior to entering the chiller at the processing facility, and every single carcass is inspected by FSIS.

Is antibiotic use in chicken production creating “Superbugs?”

As the FDA has stated, “It is inaccurate and alarmist to define bacteria resistant to one, or even a few, antibiotics as ’Superbugs‘ if these same bacteria are still treatable by other commonly used antibiotics.” For example, the strains of Salmonella Heidelberg associated with the outbreak on the West Coast in 2013 were treatable by the most commonly recommended and prescribed antibiotics used to treat infections with Salmonella.

All bacteria, antibiotic resistant or not, is killed by proper cooking.

For those antibiotics that are FDA-approved for use in raising chickens, the majority of them are not used in human medicine and therefore do not represent any threat of creating drug resistance in human pathogens. In fact, under FDA’s “judicious use” policy (in place now for years) the use of antibiotics that are medically important for treating people is permitted in food-producing animals only when used to treat a disease and only under veterinary supervision. Even before this policy, though, there was little use of medically important human drugs in chicken production. Simply put, antibiotic use in chicken production is minimal and does not contribute to antibiotic resistance.

When talking about testing raw chicken for Salmonella, what are “prevalence” and “enumeration?”

When a test is performed for Salmonella prevalence, it is looking to see if any Salmonella is present. Whether there is one, one hundred, or one thousand cells, the test will return the same result: positive. Enumeration tests for how much Salmonella is present. Some plants might utilize both methods, but current FSIS performance standards are based off prevalence.

What steps can consumers take to avoid getting sick from Salmonella?

Even though we’ve collectively made tremendous progress in reducing Salmonella on raw chicken to all-time low levels, the fact remains that any raw agricultural product is susceptible to naturally occurring bacteria that could make someone sick if improperly handled or cooked.

Given that Americans eat about 160 million servings of chicken every day, the overwhelming majority of consumers are cooking and handling chicken properly and having a safe experience.

But we want that experience to be safe each and every time. All of the tests and technology and safety procedures are for naught if the chain of safety is not maintained by consumers in the grocery store and at home, so we’ve put together some food safety tips to help:

SEPARATE

- Avoid cross-contaminating other foods. Separate raw chicken from other foods in your grocery shopping cart, grocery bags, your kitchen and refrigerator.

- Use one cutting board for fresh produce and a separate one for raw meat, poultry and seafood.

- Do not rinse raw poultry in your sink—it will not remove bacteria. In fact, it can spread raw juices around your sink, onto your countertops or ready-to-eat foods. Bacteria in raw meat and poultry can only be killed when cooked to a safe internal temperature.

CHILL

- Make raw chicken or meat products the last items you select at the store. Once home, the products must be refrigerated or frozen promptly.

- Freeze raw chicken if it is not to be used within 2 days. If properly packaged, chicken can remain frozen for up to one year. After cooking, refrigerate any uneaten chicken within 2 hours. Leftovers will remain safe to eat for 2-3 days. Refrigerators should be set to a temperature of 40°F or below.

- Thaw frozen chicken in the refrigerator—not on the countertop—or in cold water. To speed up the process, chicken can be thawed in the microwave.

- When marinating, make a separate batch of marinade to serve with the cooked chicken and discard anything that was used on the raw chicken. Always marinate chicken in the refrigerator, for up to 2 days.

- When barbecuing chicken outdoors, keep poultry refrigerated until you’re ready to cook. Do not place cooked chicken on the same plate used to transport raw chicken to the grill.

CLEAN

- Wash hands with warm water and soap for at least 20 seconds before and after handling raw chicken and after using the bathroom, changing diapers and handling pets.

- Wash cutting boards, dishes, utensils and countertops with hot, soapy water before and after preparing each food item.

COOK

- Cook chicken thoroughly. All poultry products, including ground poultry, should always be cooked to 165°F internal temperature as measured with a food thermometer; leftovers should be refrigerated no more than 2 hours after cooking.

- The color of cooked poultry is not a sure sign of its safety. Only by using a food thermometer can one accurately determine that poultry has reached a safe minimum internal temperature of 165°F throughout the product. Be particularly careful with foods prepared for children under 5, older adults and persons with impaired immune systems.

- When reheating leftovers, cover to retain moisture and ensure that chicken is heated all the way through.

For consumers, the bottom line is that chicken is safe when properly cooked and handled, and that chicken producers and processors are continually working to make them even safer. Instructions for safe handling and cooking are printed on every package of meat and poultry sold in the U.S. When these guidelines are followed, one can be assured of a safe eating experience—every time. Additional food safety information is available at fightbac.org and https://www.chickencheck.in/faq/food-safety/.